I wrote this story for Mint, around the

time of last Delhi Assembly elections which were swept by AAP. The story is

based on 2013 elections, in which AAP and BJP secured 28 and 31 seats,

respectively. It brings out how the party might have lost two seats because of

what could have been foul play - in this case deliberate use of an election

symbol, named 'Battery Torch', very similar to the party's Broom.

Mint decided not to publish it, so I am

putting it here. The peg is India Today's recent investigation (http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/uttar-pradesh-assembly-elections-dummy-candidates-india-today-expose/1/746207.html) that reveals similar

systemic rot. The story below reads very newspaper-y, for obvious reasons.

Below are photos of the two symbols -

the fake 'Battery Torch' and AAP's Broom.

Story:

If you were an AAP supporter during the

previous Delhi assembly elections, you have reason to be

worried, for you might just have unwittingly voted your party out of power, in

at least two seats.

But how could you have ever committed

the grave error of mistakenly voting for another party? It’s because an election symbol

bearing uncanny resemblance to AAP’s symbol – the Broom – was doing the rounds

in the previous Delhi election. It is noteworthy that the EVM does

not carry the name of the party, only increasing the likelihood of such a

mistake.

Later, the symbol’s capability to trick

AAP voters was taken into cognizance even by EC, which ordered its modification

for the upcoming election.

Adoption

of the Torch

symbol

|

The fact that this symbol was adopted

not by a party but by different independent candidates in as many as 29 out

of 70 constituencies in the capital, should raise still more eyebrows. The next most widely adopted symbol - cup and saucer - was adopted in only 12 constituencies.

However, before overenthusiastic

supporters jump to castigate political rivals for foul play, it is necessary

to know how election symbols are allotted to independent

candidates. Besides the symbols reserved for national and state parties, the

EC has a set of 'free symbols' which are reserved for independent candidates

as well as those from lesser known parties. These candidates are then

expected to indicate their top three preferences from among free symbols, and

in case of clashes, the final allotment is done on lottery basis.

Elaborating on the issue, a former

Chief Election Commissioner (whose name I've removed because the

story isn't for Mint anymore), said that erroneous voting due to

similar-looking symbols had indeed been a problem in the past. He, however,

added that EC had always been flexible about modifying such symbols on the

basis of any genuine complaint received, since not doing so would be an

impediment to free and fair elections. Sometimes, EC would also give its

nod to symbols demanded by candidates, if these were found acceptable.

Talking about the time when over 1000 candidates contested from Modakurichi

constituency in TN, he recalled how a judicious choice of symbols could be a

real headache for EC.

He also mentioned that despite EC's

best efforts to minimise confusion among voters, usage of dummy candidates

with similar names and symbols had been a favourite modus operandi of political parties to

cut into their rivals' vote share. He cited the example of Kuldeep Bishnoi,

who, while contesting from Hisar, faced several namesakes.

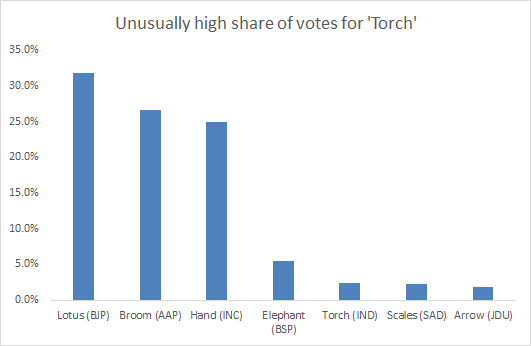

Votes polled by the symbol

While it’s difficult to establish

whether the widespread adoption of Battery Torch was politically motivated,

numbers from the above graph make clear that it was successful in diverting

votes away from AAP.

The percentage of votes polled by

Battery Torch (2.4%) was higher than that by some of the established parties,

and far higher any other symbol used by independent candidates, except ‘Glass

Tumbler’ (1.6%, not shown in the graph). However, this is only because a very

eminent candidate adopted it and went on to win the constituency of Mundka.

In case of Battery Torch, the high number of votes polled by it does not come

from one popular candidate, but from an even sprinkling of votes polled by

hitherto unknown candidates, none of whom came even remotely close to

winning. This points to a robust chance that AAP’s voters mistakenly voted

for the Battery Torch.

Did it really make a difference?

How much did the Battery Torch hurt

AAP? Assuming most votes going to this symbol were originally intended for

AAP, the party lost two seats – Kalkaji and Janakpuri – because of this

diversion. In both these constituencies, BJP was the eventual winner. In two

others, as shown in the graph, Battery Torch needed to fox only a few more

voters to turn the tables against AAP, but the party scraped through to

victory.

Had Kalkaji and Janakpuri gone to AAP,

it would have emerged as the single largest party with 30 seats, whereas

BJP’s tally would have dropped to 29.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment